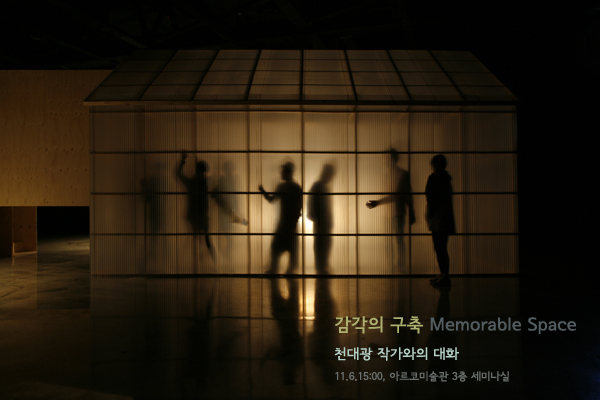

김종길

짓고 일으키는,

집 우(宇)

집 주(宙)

_ 천대광의 공간미학과 그것의 증언들

김종길 | 미술평론가

우주는 천지사방이다. 천지사방으로서의 한 세계다. 그리고 그것은 만물을 포용하는 공간이기도 하다. 천대광의 건축적이고 유기적인 조형으로서의 작업들은 이 ‘우주’의 개념에서 한 실마리를 찾을 수 있다. 나는 작품론 집필을 위해 그의 작업실을 찾아가 그와 여러 차례 만났다. 그러나 밤늦게까지 진행된 대화의 순간들은 단지 우주의 한 끄트머리를 열었을 뿐 결코 손에 잡히는 어떤 비평의 결과물들을 가져올 수 없었다. ‘천대광’이라는 한 작가를 이루는 미학적 ‘아트솔라리스’는 마치 우주가 그렇듯이 천지사방이어서 어느 것 하나로 규정할 수 없는 구조였던 것이다. 달리 말하면 그 구조는 학습된 미학의 체계로는 그릴 수 없는 탈학습의 경로였다. 그러나 분명한 것은 그의 우주가 아예 없는 것이 아닐뿐더러, 역설적으로 그 우주의 ‘(집)짓기’가 그의 미학적 실체라는 것이었다. 그래서 나는 새로 그릴 수밖에 없는 낯선 개념 몇 개로 그의 ‘짓기’를 풀어보고자 한다. 이 개념어들은 그의 작업 전반을 두루 살피면서 떠올린 것들이다. 문장 속에 등장하는 어떤 한 작품의 사례에 국한해서 읽어서는 안 될 것이다.

응[감ː응(感應)]

․ ‘응’은 ‘감응’(感應)에서 비롯된다. 감응은 ‘서로’ 응하는 것이다. 어떤 하나가 다른 하나를 주도하지 않으며 밀어내지도 않아야 한다. 그의 작품과 관객은 그렇게 감응하는 ‘교감’(交感)의 상태에서 서로 보고 통한다. 통하니 그것이 또한 응이다. 느낌을 받아 마음이 따르는 이 ‘응’의 미학은 그러므로 수평을 지향한다. 이것은 하나의 철학에 가깝다. 수평지향으로서의 ‘응’은 역설적으로 타국에서 그가 경험한 문화적 충돌에서 비롯된 바 크기 때문이다. 그는 <보청기>(2001)를 설명하면서 “서로의 음성으로 인한 묘한 에코를 경험하게 된다.”고 했다. ‘에코’는 마치, 그 작품에서 듣는 바람의 진동 소리처럼 추상적일 것이다. 에코 현상의 회오리 속에서 관객은 추상의 음성으로 교감하는 기묘한 상태를 경험하게 되는 것이다. 그것은 충돌의 갈등과 차이를 우주적(대지적일 수도 있을 터) 교감의 공간에서 ‘서로-주체’의 감응이 일어나 회통하도록 하는 초언어적 사건이 아닐 수 없다. 그의 작품들은 그런 ‘사건’이 존재하는 공간으로 가득하다.

․ ‘응’의 다른 매력은, 하나의 작품이 다른 상황 속으로 낮게 확장될 수 있는 상상력을 불러 오는 데 있다. ‘응’은 이응(‘ㅇ’) 두 개가 대지 ‘ㅡ’를 사이에 두고 위아래로 떠 있는 꼴이기 때문일지도 모른다. 그의 많은 작품들은 대지와의 관계성이 깊어서 작품이 놓이거나(장소성), 연결되거나(상호연결성/접속성), 스스로 표상되는(표상성) 경우를 종종 확인할 수 있다. 이러한 특징은 작품이 대지 위에서 무언가 우월한 (수직적) 기념비로 존재하려고 하는 미학적 위계 욕망을 해체하는 것이다. 그에게 있어 ‘표상’(表象)은 외부 세계가 아니라 ‘마음’에서 현현되는 그 무엇이어서 그것조차도 수직적이지 않다. 심리적 표상은 하나의 상징에 가까운 것이다.

“이 공간의 흐름은 한옥의 지붕이나 산의 모양 혹은 땅의 지형, 자연과 접촉했던 나의 경험에서 나온 것이다. 내가 만들어낸 공간이지만, 이미 내 안에 있었던 자연의 형상일 수 있다. 나는 그저 그 흐름을 따르고 있을 뿐이다” _ 천대광

숨[숨-결(氣)]

․ ‘숨’은 들숨날숨의 기운이다. 그의 파빌리온 작품들은 숨 쉬는 생명(체)의 결을 조형화 한 것으로 볼 수 있다. ‘숨-결’의 미학적 형상들은 심장을 싸고 있는 신경세포처럼 카오스모스적인 프랙탈 구조로 되어 있는 경우가 많다. 그 구조는 나무의 형상을 닮았으나, 건축적이다. 그런데 그는 그 형상을 만들기 위해 건축적 설계를 하지 않는다. 작품들은 상상의 흐름을 따라 드로잉하듯 연속적으로 지어질 뿐이다. 그 상상의 흐름이 미학적 설계이다. 그것을 우리는 기운(氣運)의 기화(氣化: 우주가 끊임없이 변화하는 그것으로서) 작용이라고 할 수 있다. 한 마디로, 생생화화(生生化化)로서 낳고 낳고 되고 되는 현상이다. 그것은 또 서로 의지해 함께 존재를 일으키는 연기론(緣起論)과 다르지 않다. 그는 논리적 이성의 과학적 체계 따위를 작품의 제작과정에 투입시키지 않는 것이다. 그의 사유와 행동은 차라리 만유(漫遊)에 가깝다. 작품으로서의 ‘숨’은 안팎을 나누지 않는 여유에 있고, ‘결’은 그 여유를 공진화하는 공간에 있다.

․ 그의 작품들에서 ‘숨’의 형상들은 우주배꼽을 연상시킨다. 어떤 작품이 대지에 눕거나 기대거나 섰을 때, 그 장소는 애초의 장소성과 다른 성질의 장소로 바뀌기 때문이다. 수메르어 테멘(temen)은 하늘과 땅이 하나가 되는 우주배꼽으로 ‘주춧돌’을 의미했다. ‘테멘’은 고대 그리스어 ‘테메노스’(temenos)의 어원으로 ‘(델피 신전의) 거룩한 경내’라는 의미를 갖게 되었다. 신전이 놓인 자리는 주변과 구분될 수밖에 없다. 그곳에 주춧돌이 존재한다. 그곳은 거룩하다. 천대광 작가가 실제로 제작했거나 드로잉 한 작품들은 어딘가에 놓일 주춧돌과 다르지 않아 보인다. 그리고 그것들은 숨결 가득한 ‘거룩한 경내’의 아우라를 내보이기도 한다. 수메르인들에게 ‘건축’의 의미는 “마땅히 있어야 할 자리를 찾아 그 원형을 회복하는 작업”이다. 천대광의 ‘건축-하기’도 그와 다르지 않아서 늘 마땅히 있어야 할 자리를 찾고, 이미지의 어떤 원형이 회복되는 작업을 펼친다.

*기원전 21세기 수메르의 왕 우르-남무는 지구라트를 세웠다. 1930년대에 발굴된 수메르어 비문에 따르면 “엔릴(대기의 신)의 장자, 난나(달의 신)를 위하여, 그의 왕이며, 용감한 장수, 우룩도시의 주인이며 우르 도시의 왕, 그리고 수메르와 아카드의 왕인 우르-남무가, 난나가 사랑하는 신전인 ‘에-테멘-니-구루’를 건축했다. 그는 난나를 위해 신전을 원래 있어야 하는 자리로 회복했다.”고 쓰여 있다. “원래 있어야 하는 자리로 회복했다.”는 “마땅히 있어야 할 자리로 되돌렸다.” 또는 “마땅히 있어야 할 자리를 찾아 그 원형을 회복시켰다.”로 해석할 수 있다. _ 배철현, ‘건축’, 아주경제, 2017.10.23. 참조.

“잔디밭과 길을 나란히 만들 수는 있지만, 잔디밭 위로 가로질러 난 길을 막을 수는 없다. 잔디밭 위에 난 길은 길을 설계했던 이가 예측할 수 없었던 길이다.” _ 천대광

빛[얼ː빛(光)]

․ 빛은 그의 작품에서 (관객으로 하여금) 어떤 생각 따위를 불러일으키는 환기(喚起) 장치다. 그 환기에 접속하는 순간 ‘관객’은 빛의 술수에 빠져들게 될 것이다. 자연광으로서의 빛, 인공조명으로서의 빛, 자체발광으로서의 빛, 그리고 그 모든 빛의 색과 그림자는 그의 작품이 한 장소에서 현현될 수 있는 가장 강력한 존재성이다. 빛이 없이는 어떠한 미학적 사건도 일어나지 않는다 해도 과언이 아니다. 그의 기획은 빛의 기획에서 비롯된 바 큰 것이다. <베억카멘의 하늘>(2007)에서 빛은 하늘이다. 그는 “관람객은 캐노피 아래에서 바람에 춤을 추듯 흔들리는 나뭇가지와 잎들의 그림자를 본다.”고 썼다. 그러나 춤을 추듯 흔들리는 것이 그것만은 아니다. 그 캐노피의 내부에서 관객은 ‘생각’(生角)이라는 사슴뿔을 키우기 때문이다(‘생각’의 한자어 ‘生角’은 저절로 빠지기 전에 잘라낸 사슴뿔을 뜻한다). 사슴뿔이 하늘과 접속하기 위해서는 춤을 추어야 한다(고대 퉁구스 샤먼은 사슴뿔 관을 쓰고 춤을 추면서 신을 맞이했다). 그 춤은 앞서 언급했던 만유와 다르지 않다. 어슬렁거리는 사람들, 바스락 거리는 낙엽들, 캐노피의 위와 아래를 흐르는 바람…. 거기가 생각의 거처다.

․ ‘빛’은 미학이 아니다. 빛이 미학이 되기 위해서는 (창조적) 술수의 상태를 노정해야 한다. 그의 작품들이 종종 어떤 통로의 공간으로 드러나는 것은 술수를 위한 ‘변신태’(變身態)이기 때문이다. <격자무늬터널>(2009)은 안팎을 뒤집어 놓은 우물이다. 관객은 단지 밖에서 안으로, 안에서 밖으로의 체험만을 이야기할지 모른다. 그러나 그는 들고나는 순간의 안팎 경계를 지웠고, 양 끝에 빛을 두어 시간을 이어 붙였다. 들고나는 순간의 관객 ‘나’는 동일한 주체이지만, 미학적으로 완전히 다른 주체일 수 있다. ‘(얼)빛’에 물든 주체이기 때문이다. 수운 최제우의 삼칠주(三七呪)에는 ‘시천주’(侍天主)라는 주문이 있다. “내 몸에 한울을 모셨다.”는 뜻이다. 한울은 ‘큰 얼’이기도 하고 ‘하늘’이기도 하며 그래서 ‘하느님’이다. ‘큰 얼’은 얼이 크게 밝다는 뜻이다. 그 얼이 ‘얼빛’이다. 내 몸에 큰 얼빛을 지펴서 모셔야 몸의 조화가 이뤄진다. 그것이 창조적 술수로서의 빛이다. 그의 작품들에서는 이 빛의 환기가 틈틈이 깃들어서 밝다.

“저의 철학은 단순합니다. 나를 가만히 들여다보면 내속의 화살표가 가리키는 방향이 있다. 그곳으로 가라. 잡생각은 무시하라. 그 잡생각이란 먹고 산다든지 일어나지 않은 일을 생각해내서 걱정 한다든지 뭐 여러 가지가 있겠죠. 그냥 하고 싶은걸 마음대로 했습니다.” _ 천대광

빔[공(空)]

․ ‘빔’은 공(空)과 허(虛)의 ‘다하다’, ‘없다’, ‘드물다’, ‘모자라다’ 등의 뜻을 가졌다. 그러나 그의 작품에서 ‘빔’은 ‘틈’이다. 그 틈은 빈틈이다. 이것과 저것의 사이[間]이면서 틈인 그것, 빔. 사이는 건축에서 벌어진 틈을 뜻하고, 물리적 거리를 말하기도 한다. 그러나 연극에서는 침묵이다. 고요다. 여유다. 겨를이다. 그는 작품에 ‘틈’을 주어 침묵을 개입시킨다. 여유를 짓고, 겨를의 순간들을 조성한다. 그의 작품이 ‘숨’을 얻어 ‘응’의 교감으로 살아 있는 이유는 이 ‘틈’이 숨구멍 역할을 하기 때문이다. 그의 ‘빔’은 무수한 틈들의 연합인 것이다. 그리고 그 틈의 무수한 결들이 그의 공간을 ‘인위’(人爲)에서 ‘무위’(無爲)로 이끈다. 충분히 인위적일 수 있는 작품들이 작품을 둘러싼 공간/자연과 어울리고, 또 관객들과 더불어 호흡하는 순간을 갖는 것이다.

․ 노자는 『도덕경』 제11장에서 ‘빔’의 쓸모를 말한다. 다석 류영모의 해석이다. “설흔 (낱) 살대가 한 (수레)통에 물렸으니/ 수레를 쓸 수 있음은 그 없(는 구석)이 맞아서라./ 진흙을 빚어서 그릇을 만드는데/ 그릇을 쓸 수 있음은 그 없(는 구석)이 맞아서라./ 창을 내고 문을 뚫어서 집을 짓는데/ 집을 쓸 수 있음은 그 없(는 구석)이 맞아서라./ 므로 있(는 것)이 좋음이 되는 건/ 없(는 것)을 씀으로써라.” 첫 문장을 쉽게 풀면, 서른 개의 바큇살이 한 개의 바퀴통으로 모아졌는데, 그 중간 아무 것도 없는 곳에 굴대가 끼워져 있어 수레를 쓸 수가 있다는 것. 바퀴가 잘 굴러가기 위해서는 바큇살 사이의 ‘빔’이 중요하다. 그 ‘빔’이 수레를 쓸모 있게 하는 것이다.

“나는 예술을 통해 도를 닦는다. 도를 찾아가는 방식은 수도 없이 많다고 생각한다. 그런 의미에서 작업은 내가 삶을 찾아가는 한 방식이다. 사람들이 나의 노동에 대해서 ‘힘들지 않느냐?’고 하는데, 나는 작업을 하면서 논다. 작업을 하지 않는 동안 내 상태는 ‘완전한 쉼’의 상태가 아니다.” _ 천대광

짓다/일으키다[作]

․ ‘짓다-일으키다’의 ‘작’(作)은 근대 이후 예술의 행태적 개념으로 완성되었다. 그러나 그것은 어떤 (미학적) 사태의 결과로서 결코 ‘완성’될 수 없는 생기론적 개념이라 할 것이다. 그래서 현대미술에서는 그것을 ‘수행성’의 개념으로 해석하기도 한다. 과정으로서의 예술일 수 있으니까. 생기론(生氣論, vitalism)의 활력은 ‘품’(品)에 깃들어서 품의 성향을 돋우지만, 그 성향이 곧 품은 아니다. 그렇다고 그 성향을 ‘작’이라 할 수도 없다. ‘작’은 결과론적인 ‘품’의 행태론에 앞서 있는 ‘~되기’의 작용이기 때문이다. 그런 맥락에서 천대광 ‘작/품’(作/品)의 무게는 ‘작’에 있을 것이다. ‘품’은 지어서 일으킨 ‘작’의 결과물로만 존재할 뿐이고. 다시 말해 그는 결코 ‘품’의 완성을 위해 ‘작’을 가벼이 하지 않는다.

․ 혜강 최한기의 ‘운화지기’(運化之氣)로 ‘작’을 개념화 할 수 있다. ‘운화지기’는 ‘기’가 곧 활동운화라는 얘기다. 그는 ‘운화지기’의 본성과 본능을 설명하면서 “물체가 있으면 반드시 그 물체의 본성과 능한 바가 있으니 작은 물체는 소성소능(小性小能)이 있고 큰 물체는 대성대능(大性大能)이 있다. 대저 기라고 하는 것은 견줄 곳이 없을 만큼 커서 이 기가 쌓이면 힘이 생기고 운화하면 신령스러운 작용이 생긴다. 그러니 바로 이러한 것이 기의 본성이요, 기의 능한 바이다.”라고 한 것이다. 천대광의 제작 과정은 그의 몸과 마음이 활동운화의 총화인 것을 드러내는 순간들이다. 마치 ‘기의 본성’이 발현되는 순간들처럼 그는 짓고 일으키는 ‘작’의 순간들에 몰두하기 때문이다. 그의 작품들은 그 ‘작’의 미세한 사건들이 모여서 이룩한 우주다.

“세상의 만물이 끝없이 변화하는 것처럼, 예술도 진화한다. 여기서 진보라는 말은 어울리지 않는다. 그렇기 때문에 예술은 한 시대의 제도적 약속에 머물러 있어서는 안 된다. 내 작업도 예술의 약속이나 제도적 진화과정을 유추해서 움직이는 예술이 아니라 그 흐름에서 독자적인 삶의 에너지를 만들어 갈 수 있는 움직임이었으면 좋겠다. 하지만, 동시대 젊은 작가들은 자신의 내적 동기와는 무관하게 동시대 예술의 흐름과 유행을 의식하고 그 안에 들어가려고 노력한다. 그것이야 말로 무의미한 것이다.” _ 천대광

풍류[즐기다(樂)]

․ ‘풍류’(風流)는 ‘부루’다. 고유사상으로서의 부루는 ‘불 ․ 밝 ․ 환 ․ 하늘’을 가리킨다. 그 말들에 신성이 깃들어 있는 것이다. 그래서 풍류는 속된 것을 버리고 고상한 유희를 하는 것으로 풀이되기도 하고, 풍치가 있고 멋스럽게 노는 일, 또는 자연과 인생과 예술이 혼연일체가 된 삼매경을 뜻하기도 한다. 그의 작업들은 스스로 즐기는 미적 체험으로서의 풍류에 있을 것이다. 그는 흐르듯이 걷고 걷듯이 말한다. 그와의 대화는 그래서 한 자리로 돌아오지 못하고 빙빙 에둘러 어느 새 우주에 가 있는 경우가 허다했다. 작품들은 그렇게 ‘노는 일’의 유희적 풍치에서 발현되었을 것이다. 다석 류영모는 ‘나’란 이 우주의 끄트머리인 한 ‘긋’[點]이라고 했다. 그는 종종 그 ‘긋’에서 온 사람처럼 말하고 행동하고 지었다.

․ ‘긋’의 사전적 의미는 ‘획’이다. 글씨나 그림에서 붓 따위로 한 번 그은 줄이나 점인 것이다. 주시경은 ‘끝’을 ‘긋’이라 표기하기도 했다. 다석의 ‘긋’은 낱생명으로서의 ‘나’를 가리킨다. ‘끝’이 끄트머리이니, 한 번 그은 점의 끝이 곧 ‘긋’이요, ‘나’일 수 있다. 그렇다면 ‘나’를 어디로 그어야 할까? 어디로 그어서 한 긋이 될 수 있을까? 마음을 다해야 우리는 한 긋이 될 수 있지 않을까? 천대광의 사유는 늘 ‘생각의 긋’에 있을 것이다. 그 긋의 온전한 표현이 또한 그의 작업일 테이고. 우리는 그 자신의 ‘긋’이 하나의 집[宇宙/空間]을 이룬 곳에서 그와 마주하게 될 것이다.

“내가 만들고 싶은 모양은 내가 고안하기 이전에 이미 거기에 있었고, 내가 손에든 재료의 탄성 안에 이미 들어있었다. 나는 공간이 가르쳐 주는 대로 작업하고 재료가 인도하는 대로 못질한다. 태껸이나 가야금의 선율이 자연스러운 몸짓과 운율을 따르는 것처럼, 내 공간들의 표면은 그렇게 주변의 자연과 공간의 표면을 타고 흐른다.” _ 천대광

그림자[반영(反影)]

․ 현실의 밑에 서린 그림자들, 기억의 밑에 어린 그림자들, 시간의 밑에 쌓인 그림자들…. 그의 작품 중에는 그런 그림자 공간을 ‘집’으로 해석한 것들이 있다. <뒤틀린 공간>(2008), <유주의 삶(의도되지 않았던 삶-우리는 어디에서 와서 어디로 가는가?)>(2011), <집, 통로 그리고 출구>(2013) 등이 그것이다. <뒤틀린 공간>은 2008년 당시 경기도 안산의 원곡동 ‘국경 없는 마을’에 위치한 커뮤니티스페이스리트머스의 지하에 둥지를 틀 듯 공간을 만든 것이다. 그 지하는 마치 지상의 다국적 이주 노동자들의 상황을 되비추듯(백기영은 “반듯하고 평평한 인위적인 사물들이 뒤덮인 우리 삶의 공간에서 천대광은 뒤틀리고 울퉁불퉁하며 불규칙적인 표면들을 상상”했다고 말한다.) 뒤틀려 있었다. 바람이 지나간 우물의 표면처럼, 파도가 휩쓸고 간 연안의 절벽들처럼 공간은 심하게 일렁였다. 그 일렁임의 긴장은 나무 하나하나의 탄성에서 비롯된 것이다. 그 공간은 그렇듯 탄성이 빚어낸 ‘집’이었다. <유주의 삶>은 경기도 안산 대부도 갯벌에 쓰러질 듯 정박해 있는 폐선(廢船)을 경기창작센터로 운반해 ‘집’의 터(바닥)와 몸(내부)으로 바꾼 것이다. 시간의 그림자조차 허물어진 배가 ‘집’이 되었을 때 그림자는 투명하게 되살아났다. <집, 통로 그리고 출구>는 그의 기억에서 비롯되었다. PVC슬레이트와 목재, 조명, 거울, 백열등, 물을 이용해 지은 ‘집’은 허술했다. 가벼웠다. 그러나 모든 기억들이 그렇듯 그 가볍고 허술한 것의 원인은 ‘환’[幻ː影]이 작동하기 때문이다.

․ 라마나 마하리쉬(Ramana Maharishi, 1879~1950)의 『나는 누구인가』를 번역했던 지산 스님이 2010년 입적하면서 마지막으로 남긴 글은 “삶은 꿈이다.”로 시작되는데, 뒤이어 그는 “중생들의 삶이란 탐·진·치가 빚어내는 꿈이요 환”이라고 썼다. 마하리쉬의 어록에 만약 ‘나’ 또한 하나의 환이라면 그 환을 벗어던지는 것은 누구인지를 묻는 장면이 있다. 그는 이렇게 답했다. “‘나’가 ‘나’라는 환을 벗어던지지만 그러면서도 ‘나’로서 남아있다. 이런 것이 참 나에 대한 깨달음의 역설이다. 그러나 깨달은 자는 거기서 어떠한 모순도 보지 않는다.” 그런 다음 이렇게 덧붙인다. “환의 산물인 이스와라(Isvara: 순수 존재의식)가 실재하지 않는 것은 잠의 산물인 꿈속의 대상들이 실재하지 않는 것과 같다. 그는 무지의 산물인 개아(開我), 혹은 잠의 산물인 꿈속의 대상들과 같은 범주이다.” 이 말의 핵심은 ‘내가 있다’는 것에 대한 순수한 깨달음이다.

․ 천대광은 욕망이 세운 도시에서 ‘환의 세계’을 엿본다. <견인도시 프로젝트>는 환의 그림자가 실체를 얻어 탄생한 건축의 구조와 껍질을 채집하고 교배시키는 미학적 실험이다. 필립 리브의 소설 『견인 도시 연대기』에서 개념을 차용했다. 그는 이 프로젝트를 전 생애에 걸쳐 진행하게 될 장기프로젝트라고 밝혔다. 소설은 전쟁으로 초토화 된 3천년 후의 세계가 배경이다. 그 세계는 캐터필러 바퀴로 굴러가는 ‘견인도시’(Traction City)의 난투장이다. 도시가 도시를 집어삼키는 도시 진화론의 지옥이 펼쳐지고 있는 것이다. 도시가 도시를 삼키는 장면은 그에게서 건물이 건물과 교배하는 방식으로 재구성된다. 그 과정을 거쳐 그는 도시 전체를 재사유하는 ‘환의 도시혁명’을 꿈꾸고 있다. 이러한 사유의 밑바탕에는 ‘나 혹은 우리는 누구인가’에 대한 본질적인 질문이 깊게 깔려 있는 듯하다.

그의 작업은 수행과 같아서 예술의 이름으로 규정할 수 없는 곳에 위치한다. 예술의 이름으로 규정할 수 없는 것이 새로운 예술일 것이다. 그리고 그런 예술이 곧 전위가 아닐까. 그렇다고 그가 어떤 전위를 획득하기 위해 전위예술을 기획하고 있다고는 보이지 않는다. 그의 삶은 온통 ‘내가 있다’는 이스와라의 실재를 깨닫는 것에서 비롯되는 듯하다. 그러므로 그에게는 하루하루가 새로운 시작일 것이다. 하루하루의 환의 실재와 싸우는 순간들이기도 할 터이고. 나는 잠시 그 순간들 속에서 그가 지은 집들을 보았던 게 아닐까 싶다. 그 또한 환일지도 모르는 일이고. 그러나 분명하는 것은 이곳이 ‘잠의 산물’은 아니라는 것이다. 나는 바로 그것이 환의 미명을 깨는 천대광의 화두라고 생각한다.

To Build and to Raise,

House Wu(宇)

House Ju(宙)

- Dai Goang Chen’s spatial aesthetic and its statements

Jong-gil Gim (Art Critic)

The universe expands in all directions; it is a world upon all directions. It also is a space that embraces every creations of nature. A lead for Dai Goang Chen’s architectural and systematic works can be found in this concept of the ‘universe.’ I visited Chen’s studio numerous times to prepare my writing. However, the moments of conversations lasting until late at night merely opened a small edge of the universe, and was not able to bring any results of critique. The aesthetic ‘Art Solaris’ that forms ‘Dai Goang Chen’ as an artist is in all directions like the universe, so it is a structure that cannot be defined with one idea. In other words, the structure is a path that cannot be painted with a trained system of aesthetics. What is clear here, however, his universe does exist, and ironically, that universe’s ‘(house) act of building’ itself is his aesthetic reality. Therefore I am attempting to analyze Chen’s ‘act of building’ through a few unfamiliar concepts. These conceptual terms were thought out while thoroughly examining Chen’s works, and should not only be read limited to the work mentioned in the paragraph.

Eung (응, To Respond) [Gam-Eung (감응, To Empathize, 感應)]

‘Eung (응, to respond)’ originates from ‘gam-eung (감응, to empathize, 感應).’ Gam-eung is to respond to one another. One must not lead, nor push away. Chen’s works and the audience communicate with one another under the state of ‘Gyo-gam (교감, connection 交感.)’ To connect is to respond. The aesthetic of ‘eung (응, to respond),’ in which one feels then the mind follows, pursuits balance. This is close to a philosophy, because the balance-directional ‘eung (응, to respond)’ ironically originates from Chen’s experience of cultural collision in foreign countries. While explaining his work, Das Hörrohr (2001), he mentions, “You can experience an obscure echo caused by the voice of others.” ‘Echo’ is abstract like the vibration of wind in his work. The audience experiences the strange phenomenon communing through abstract sounds in a whirlwind of echo. This is an event that transcends language, to correspond to conflict and differences of collision, through empathy between ‘another – self’ in the space of cosmic (even earthly) communion. His works are full of spaces with this kind of ‘events.’

Imagination of one work expanding to different circumstances ignited by ‘Eung (to respond)’ is another attraction of it. Perhaps it is because ‘Eung (응, to respond)’ is formed with Korean alphabet, ‘ㅡ (earth)’ between two ‘ㅇ.’ Many of Chen’s works have a relationship with the earth, as they have sense of place, interconnectivity/connectedness, and self-symbolism. These characteristics dismantle the desire for aesthetic hierarchy of the work that attempts to exist as something superior on the earth. For Chen, ‘Pyo Sang (표상, symbol, 表象)’ is something that manifests from the ‘mind,’ not the outer world, therefore not even that is vertical. Psychological symbolism is similar to a representation.

“The flow of this space comes from Hanok (traditional Korean house), the shape of a mountain, geography of land, or my experience with nature. Although the space is created by me, it is the form of nature that was already inside me. I only follow that flow.” – Dai Goang Chen

Sum (숨, Breath) [Sum-Gyul (숨-결, breath, 氣)]

‘Sum (숨, breath)’ is the energy of inhaling and exhaling. Chen’s pavilion works materializes the ‘gyul (결, energy from breathing)’ of living life. The aesthetic forms of ‘sum-gyul (숨-결)’ mostly have chaosmos-like fractal structures like nerve cells covering the heart. This structure resembles the form of a tree, but is architectural. However, Chen does not design architecturally to create this form. He only builds as if he is drawing, following the flow of imagination. This flow of imagination is the aesthetic design. We may call it the evaporation of vitality (氣運). Simply put, it is like ‘seng-seng-hwa-hwa (生生化化)’, producing and becoming. This also is not different from ‘yeon-gi-ron (Falsification theory, 緣起論),’ which wakens the existence together relying on each other. Chen does not insert a scientific system of logical reason in his work’s production process. His ideas and behavior are rather closer to ‘man-yu (freely traveling, 漫遊).’ ‘Sum (숨, breath)’ as an artwork is in the stability that does not divide inside and outside, and ‘gyul (결, energy from breathing)’ is in the space coevolving that stability.

The forms of ‘sum (숨, breath)’ in Chen’s works resemble the navel of the universe. This is due to when an artwork is lying flat, leaning, or standing on the earth, that location transforms into a different place with a different quality from the original space. ‘Temen,’ a Sumerian word for ‘cornerstone’ signifies the navel of the universe in which heavens and the earth become a unity. ‘Temen’ is the origin of ‘temenos,’ an ancient Greek word, and signifies sacred sanctuary. The location of a sanctuary is different from its surroundings, and the cornerstone exists in that location. It is sacred. The works that Chen has created feel similar to the cornerstones that would be placed somewhere. And they have the aura of a ‘sacred sanctuary.’ ‘Architecture’ for Sumerians meant “searching for a place something should properly be, and restoring an original form of an image.” Chen’s ‘architecture-doing’ is no different from this.

* In 21st century BCE, Ur-Nammu, king of Sumer, built the ziggurat. In a Sumerian epitaph excavated in the 1930s, it states, “for Nanna (god of the Moon), son of Enil (god of the wind), Ur-Nammu, their king, mighty warrior, master of Uruk, king of Ur, and king of Sumer and Akkad, built ‘en-temen-ni-guru.’ He has returned the sanctuary to the place it belongs for Nanna.” “Returned to the place it belongs” can be interpreted as “returned to the place it deserves” or “searched for its rightful place and restored its original form.” – Chul-Hyun Bae, ‘Architecture,’ Aju News, 2017.10.23

“One can make a lawn and road side by side, but cannot stop the road traversing the lawn. The road traversing the lawn is something the designer could not predict.” – Dai Goang Chen

Light [Eul (Spirit, Soul)–Light (光)]

Light in Chen’s work is a stimulation (喚起) device that remind ideas and thoughts. The moment the ‘audience’ touch that stimulation, they will sink into light’s stratagem. Light in different forms such as natural light, artificial light, self-radiating light, and the colors and shadows of all these lights are the strongest existences his works may manifest in a single space. Aesthetic events can never happen without light. Chen’s design plan begins from light. The light in Bergkamen of the Sky (2007) is the sky. Chen wrote, “The audience sees the shadow of the swaying tree branches and leaves, as if dancing with the wind, under the canopy.” However, these are not the only things swaying as if dancing with the wind, because the audience raises an antler called ‘Saeng-gak (idea, thought, 生角)’ under the canopy. (The Chinese symbol for ‘Saeng-gak (idea, thought, 生角)’ indicates an antler, cut off before it naturally falls off.) For the antler to touch the sky, it needs to dance. (Proto-Tungusic shamans welcomed gods by dancing with antler head dresses.) That dance is no different to ‘man-yu (freely traveling, 漫遊) mentioned above. The wandering people, rustling leaves, the wind that flows throughout the canopy… this is the home of thoughts.

Light is not an aesthetic. For light to become an aesthetic, it needs to be exposed to (creative) stratagem. The reason Chen’s works frequently appear to be passages is, that they are a ‘byun-shin-tae (camouflage, 變身態) for stratagems. A Coffer Patterned Tunnel (2009) is an inside-out well. The audience may only speak of the experience from outside to inside, and inside to outside. However, Chen has erased the boarder of the interfering moment, and placed light on both ends to connect time. The audience, ‘I’ of the interfering moment is identical, but may be completely different aesthetically, because it is stained with ‘(eul (spirit)) light.’ Shi-chun-ju (侍天主) is an incantation in Su-Eun Choe Je-u’s Sam-chil-ju (twenty-one prayers, 三七呪). Shi-chun-ju (侍天主) means “my body enshrines the Han-eul.” ‘Han-eul’ can be a ‘large eul (spirit, soul)’ and ‘the sky,’ and therefore is ‘god.’ ‘Large eul (spirit, soul)’ means the eul is magnificently bright. This eul is the ‘spirit-light.’ One may achieve harmony in the body once a ‘large eul’ kindles within. This is the light as creative stratagem. Chen’s works are bright, because this stimulation of light indwells in them.

“My philosophy is simple. Once I look into myself, an arrow inside is pointing at a direction. Go there. Ignore distractive thoughts. These distractive thoughts may be everyday life or concerns of things that never even happened. I just did things that I wanted to do. - Dai Goang Chen

Bim (빔, Emptiness) [Gong (공, vacant, 空)]

‘Bim (빔, emptiness)’ has intricate meanings such as ‘finished,’ ‘not present,’ ‘not enough,’ and many more, of gong (vacant, 空) and heo (hollow, 虛). However, in Chen’s works, ‘bim (빔, emptiness)’ means ‘teum (틈, gap).’ This gap is an empty gap. ‘Bim (빔, emptiness)’ is the ‘in between (間)’ and gap of this and that. In between signifies the gap between two buildings or physical distance. However, it is silence, tranquility, composure, and leisure in theatre. Chen gives gaps to his works and intervene silence. He builds composure and constructs moments of leisure. The reason his works have ‘sum (숨, breath)’ and lives through the communion of ‘eung (응, to respond),’ is because this ‘gap’ acts as ventilation. His ‘bim (빔, emptiness)’ an alliance of numerous gaps, and the numerous ‘gyul (결, energy from breathing)’ inside leads Chen’s spaces from ‘artificial (人爲)’ to ‘natural (無爲).’ The works that could be artificial gets a moment to harmonize with its surrounding space/nature, and to breathe together along with the audience.

Laozi explains the usage of ‘bim (빔, emptiness)’ in Tao Te Ching, chapter 11. “Thirty spokes unite around one hub to make a wheel. It is the presence of the empty space that gives the function of a vehicle. Clay is molded into a vessel. It is the empty space that gives the function of a vessel. Doors and windows are chiseled out to make a room. It is the empty space in the room that gives its function. Therefore, something substantial can be beneficial. While the emptiness of void is what can be utilized.” The first sentence simply put, the reason the wagon can be used is, thirty spokes gather in a wheel, and a spindle is put in the empty center. For the wheel to spin with ease, the ‘bim (빔, emptiness)’ in between the spokes is important. This ‘bim (빔, emptiness)’ makes the wagon useful.

“I cultivate myself through art. There are so many ways to cultivate myself. In this sense, working is a way for me to seek the meaning of life. People ask if my work is hard, but I ‘play’ as I work. I am never ‘resting completely’ when I am not working.” - Dai Goang Chen

To Build/To Raise (作)

‘Jak (to build/to raise, 作)’ has completed as a behavioral concept of post-modern art. However, it is a vitalism concept that cannot be ‘completed’ as result of certain states. Thus, contemporary art interprets it as a concept of ‘practice.’ It could be art as process. The energy of vitalism (生氣論) indwells in ‘peum (품, object, 品)’ and arouse the propensity of it, but the propensity is not ‘peum (품, object, 品)’ itself. But that does not mean this propensity can be said to be ‘jak (작, to build/to raise, 作)’ either, because it is an effect of ‘becoming something’ in front of the result of the behaviorism of ‘peum (품, object, 品).’ In this sense, ‘jak (작, to build/to raise, 作)’ weights more in Chen’s ‘jak-peum (작품, artwork, 作品).’ ‘Peum (품, object, 品).’ Is merely a result of ‘jak (작, to build/to raise, 作)’.

‘Jak (작, to build/to raise, 作)’ can be conceptualized with Hyegang Choi Han-gi’s ‘Un-hwa-ji-gi (運化之氣),’ which indicates that ‘gi (vitality, 氣)’ is ‘constantly moving and changing.’ While explaining the essence and instinct of ‘Un-hwa-ji-gi (運化之氣),’ Hyegang Choi Han-gi deems, “If there is an object, there is a certain essence and ability of that object. Generally, ‘gi (vitality, 氣)’ is incomparably large, and power is created when it cumulates, and divine effect forms when it lives. This is the essence of ‘gi (vitality, 氣),’ and its greatest ability.” Chen’s working process is composed of moments that reveal that his body and the mind is a unity of constantly moving and changing life. He devotes himself in moments of ‘jak (작, to build/to raise, 作)’, like the moments in which the essence of ‘gi (vitality, 氣)’ is manifested. Chen’s works form a universe, erected with fine events of ‘jak (작, to build/to raise, 作).’

“Like all creation of the world change endlessly, art evolves. Here, ‘advance’ does not do justice. Art should not remain in a institutional engagement of a generation. I hope my work is a movement that can create unique vitality of life in the flow of evolution, instead of analyzing it. However, contemporary young artists are conscious of the flow and trends of contemporary art, and attempt to be included, regardless of their inner motives. This is meaningless.” - Dai Goang Chen

Poong-Ryu (풍류, Taste for the Arts, 風流) [Enjoyment (樂)]

‘Pung-ryu (taste for the arts, 風流)’ is ‘buru (부루, brilliant).’ ‘Buru’ as distinct idea, signifies ‘fire, brightness, shine, and bright sky.’ The words are indwelled with sacredness. Thus, ‘pung-ryu (taste for the arts, 風流)’ at times is interpreted as neglecting worldly things and entertaining with elegance, playing beautifully, or complete unity of nature, life, and arts. Chen’s works are ‘pung-ryu (taste for the arts, 風流)’ as self-enjoying aesthetic experience. He walks as if flowing, and speaks as if walking. Conversations with him never stayed in one subject, and always went in all directions. His works probably began from the elegance of ‘playing.’ Daseok Lyu Yeongmo deemed that ‘I’ is merely a ‘geut (긋, point, stroke, 點)’ in this universe. Chen frequently spoke and behaved like a person from this ‘geut (긋, point, stroke, 點).’

The lexical meaning of ‘geut (긋, point, stroke, 點)’ is ‘stroke.’ It is a stroke of line or point in writing or painting. Ju Si-gyeong used ‘geut (긋, point, stroke, 點)’ to indicate ‘end.’ Daseok’s ‘geut (긋, point, stroke,點)’ signifies the ‘I’ as a singular life. ‘End’ is a tip, and the end of a stroke of point is ‘geut (긋, point, stroke,點),’ and ‘I.’ Then where should ‘I’ be stroked towards? How can it be stroked to become a ‘geut (긋, point, stroke,點)?’ Should we not make the stroke with all our heart to become a ‘geut (긋, point, stroke, 點)?’ Chen’s idea is always in the ‘stroke of thought.’ The intact expression of this ‘geut (긋, point, stroke, 點)’ is his work itself. We will meet him where his ‘geut (긋, point, stroke, 點)’ becomes a house (宇宙/空間).

“The form I wish to create has already existed before I design it, and was already in the elasticity of the material in my hands. I work as the space teaches me, and I nail as the material guides me. As Taekkyeon (traditional Korean martial art) or the tune of a Gayageum (traditional Korean instrument) follows the natural gestures and rhythms, the surface of my spaces follows the flow of the surrounding nature and space.” - Dai Goang Chen

Shadow [Reflection (反影)]

The shadows casting under reality, memory, and time… Some of Chen’s works interpret these shadows as ‘houses’ such as, Twisted Space (2008), Yooju’s Life (2011), House, Passageway, and Exit (2013). Twisted Space (2008) was placed in the basement of Community Space Litmus in ‘Borderless Village’ at Gyeonggi-do. The basement is twisted as if it reflects the multicultural immigrant laborer’s reality above ground. (Baik Gi-young says that “Chen imagined the twisted, rough, and irregular surfaces in our life, filled with straight and flat artificial objects.) The space swayed severely like the surface of a well after a windstorm or the cliff in a shore after a shower of intense waves. The tension of this swaying begins from the elasticity of every single wood. The space is a ‘house’ made with elasticity. In Yooju’s Life (2011), Chen transports an abandoned ship from Daebudo at Gyeonggi-do, to Gyeonggi Creation Center, and transforms it into a site (floor) and body (interior) of a ‘house.’ When the ship, with crumbled shadow of time, became a ‘house,’ the shadows transparently revived. House, Passageway, and Exit (2013) begins from Chen’s memories. Built with wood, lighting, mirror, incandescent light, and water, this ‘house’ is feeble and light. However, like all memories, the effect of ‘hwan (환, apparition, 幻ː影)’ is the reason for the feebleness and lightness.

The last words of the late Buddhist monk Jisan, who translated Ramana Maharshi’s (1879 – 1950) Who Am I?, starts with “Life is a dream.” Then he says, “the life of all living things is a dream and ‘hwan (환, apparition, 幻ː影),’ made with greed, anger, and foolishness. Once Ramana Maharshi was asked who could get rid of ‘hwan (환, apparition, 幻ː影)’ if ‘I’ is yet another, he answered, “Even when ‘I’ get rid of ‘hwan (환, apparition, 幻ː影),’ ‘I’ am still ‘I.’ This is the irony of my enlightenment. But the enlightened does not see a contradiction here. The nonexistence of Isvara (special self), the fruit of ‘hwan (환, apparition, 幻ː影)’ is like the dream, the fruit of sleep, is not real. This is the same idea as ‘gae-a (개아, idea of self, 開我),’ the fruit of ignorance, or dream, the fruit of sleep.” The core of his answer is the pure enlightenment towards the ‘existence of I.’

Chen peeks into the ‘world of hwan (환, apparition, 幻ː影)’ in a city built by desire. Traction City Project is an aesthetic experiment where he collects and breeds the structure and shell of the architecture created by the shadow of ‘hwan (환, apparition, 幻ː影)’ gaining real existence. Chen borrowed the concept from Philip Reeve’s novel, Traction City (2011). Chen proclaimed that this will be a long-term project, that will progress his lifetime. The novel takes place in the world burned to the ground from war, 3,000 years in the future. This world is a battle field of Traction City, run by caterpillar wheels. The hell of evolution theory of city, where a city swallows another, takes place. Chen reconstructs the scene where a city swallows another into the mating of buildings. Through this process, Chen aspires a city revolution of ‘hwan (환, apparition, 幻ː影)’ that revisions a whole city. It seems that the fundamental question, “who am I, and who are we?” is deeply buried in the background of this idea.

Chen’s work is like asceticism, and therefore is undefinable with the name of art. Perhaps something undefinable with the name of art, is the new art, and avant-garde. Nevertheless, Chen does not perform avant-garde art to attain a kind of potential. All aspects of his life begin from perceiving the existence of Isvara. Therefore, every day is a new beginning, and moments fighting the existence of ‘hwan (환, apparition, 幻ː影)’ for him. I think I witnessed the houses he has built in those moments for a while. Perhaps this is an apparition as well. What is certain, however, is that this is not a ‘product of sleep.’ I believe that this is the subject of Chen that breaks the good name of ‘hwan (환, apparition, 幻ː影).’

FAMILY SITE

copyright © 2012 KIM DALJIN ART RESEARCH AND CONSULTING. All Rights reserved

이 페이지는 서울아트가이드에서 제공됩니다. This page provided by Seoul Art Guide.

다음 브라우져 에서 최적화 되어있습니다. This page optimized for these browsers. over IE 8, Chrome, FireFox, Safari